READING TIME 10 minutes

Origin Story

This work came about as a natural extension of our own experiences being part of and working with highly at-risk groups. Natalie is an archivist and ethnographer working at the nexus of human rights, technology, and design. Caroline Sinders is a technologist and artist who examines the impact of technology on society, focusing specifically on interface design, artificial intelligence, abuse, and politics in digital conversational spaces.

At RightsCon 2018, a number of human rights defenders working at every stage of the research → development process came together to create the Secure UX Checklist because there was no roadmap that addressed the challenges we faced in our digital freedom work. We created this for ourselves and others working with at-risk communities, including: designers, human rights activists, public interest technologists, hackers, localizers, researchers, and tool-builders. Inspired by this work and others in our community who appreciated the checklist and needed a roadmap to implement it, we designed this methodology. Our curriculum acknowledges and builds on the work of other experts who aim to create a safer, more inclusive, human rights-focused digital world.

The Importance of This Work

Regardless of your background, this curriculum can help you identify and unpack some of the problems created by big technology and software platforms and share preventive strategies for how to work responsively and responsibly with those at-risk to create safer, usable tools and resources. To better understand the current tech crisis that we are responding to, Silicon Values by Jillian C. York does a deep dive into its origins.

We aim to help you learn how to center human rights throughout your entire research, ideation, building, iteration, and release processes. While this guide is created by and for human rights activists, we hope that it will percolate beyond the human rights space to those who want to improve the safety and security of their communities and stakeholders when building resources and tools. As Edward Snowden said, "Arguing that you don't care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don't care about free speech because you have nothing to say.

Technology Design is Not Neutral

Technology design has often been understood as strictly mechanical, divorced from the social and political landscape. In recent years, however, an increasing number of activists, scholars, and designers have called this belief into question, contesting the idea that design is a neutral act. Animated by these discussions, we see design as a social and political act. By informing the way technologies are utilized, design influences the actions of its users and the arena of social relations in which its users participate. The design of an internet platform, for example, may encourage interaction among strangers or incentivize widespread data collection. In the context of human rights activism, the stakes of technology design are uniquely high: activist-oriented technology can be structured to protect privacy, earn consent, and encourage civil dialogue, or it can furnish personal data to authoritarian regimes, catalyze the spread of misinformation, and incentivize interpersonal abuse.

The Call for Human Rights Centered Design

We believe that digital rights are human rights. Human Rights Centered Design (HRCD) is a set of research, design, and product development methodologies that combine human centered design with human rights policy. It is a response to the global abuse of people’s privacy and rights online and off: internet censorship, bias in technology, online harassment, adversarial state actors engaging in cyberwarfare and many other events that degrade or challenge general human rights.

As human rights centered designers, we ask how can human rights activists design their technologies in a manner that promotes ethical use, minimizes abuse potential, and aligns with community principles and practices? This is the question we strive to answer in the following chapters.

Our approach to this question builds on the principles of human rights law, participatory design, and the build-it-yourself ethos of internet activism. "Nothing about us without us" is a guiding credo within our human rights centered design methodology. This approach focuses on how to bring rights, equity, and collaboration into every aspect of the design through development processes. We believe that, in order for a process to be inclusive, ethical, and human rights-focused, it must consider the needs and abilities of its audience at every stage.

- Integrates human rights directly into the lifecycle of RDD

- Centers the needs of communities

- Security-focused: ensuring the protection of users is key, recognizing that security and safety are fundamental human rights

- Accessibility: the tools should be localized and context-specific so they are usable and accessible to the communities they serve

- Innovative workflow that is responsive and adaptable to communities’ needs

- Engages in cooperative and collaborative co-design (moves beyond participatory design)

- Appreciates plurality of knowledge creation and understands that the expert is an individual, a community, a coalition, an activist, a cooperative, a researcher, and an academic, e.g. the expertise is accessible to everyone, and it exceeds the boundaries of traditional institutions that purport to wield special authority over

- knowledge production

- Public / community intelligibility: it makes information broadly intelligible by avoiding jargon and unnecessary complexity

Based on these principles, HRCD aims to center the communities we serve in order to deeply understand their needs and mitigate threats they face with our work. Our goal is to take a more equitable, intersectional, feminist, and human rights-focused approach.

The Conventional View of Design

Design touches almost everything in our daily lives — our kitchen chairs, our state's governing principles, and the apps we routinely use. Digital systems continue to grow in popularity, wielding ever-greater influence on how we connect with each other and how we complete simple tasks. Most current digital design processes are based on a set of standards and protocols that derive from a methodology devised by Silicon Valley engineers in the 1980s and popularized in the 1990s: human-centered design “is an approach to problem-solving commonly used in design, management, and engineering frameworks that develops solutions to problems by involving the human perspective in all steps of the problem-solving process.”

Critiques of the Conventional View of Design

Originally understood as a universal set of technical principles, human centered design covertly reflected the particular values, preferences, and worldviews of its (white, male, and affluent) Silicon Valley architects. As designers and scholars have recently demonstrated, these values have become hard-wired into the operability of ubiquitous digital technologies. This can clearly be seen in how facial recognition technology has difficulty in distinguishing different genders and races, but tests most accurately with white, male faces.

As Professor Ahmed Ansari explains, “No toolkit, book, lecture or workshop opens without a clarification or homage to these two terms.” Reflecting on the introduction of design thinking into the Pakistani technology community, Ansari notes how the imported paradigm appeared to the community as universal and uncontested, "divorced from its larger history and the kinds of debates happening around it in the Global North.” The spread of Western design thinking, Ansari argues, has come to undermine the region's “traditional ways of practicing design.” It has also meant the spread of those values embedded in design thinking, which thus functions as a kind of proxy intellectual colonizer.

The concept of HRCD emerged as a response to how human centered design fails the most vulnerable in our society. The notion that design is universal, or applicable across contexts and insulated from social forces, remains a widespread misconception. Design must be oriented to meet the specific needs of users in an array of divergent circumstances. It must be adapted to the unique purposes that the designed technology is meant to fulfill. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the question of design, and the desire to simplify the design process through the creation of uniform standards is largely counterproductive and often destructive, as the disconnect between universal design principles and local social conditions undermines the value of the designed technology and creates opportunities for its systematic misuse.

We need design practices that are responsive to the variety of circumstances within a complex society and the variety of needs within a diverse population. When design reflects the multiplicity of people using the technology, it can effectively benefit the communities it serves. To bridge the divide between what design is and what it needs to be, we propose a transition from human centered design to human rights centered design.

In order to fully understand HRCD, we must first explore its roots in human rights policy.

So What is Human Rights Policy?

Enshrined in the United Nations 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), human rights law protects fundamental political rights afforded to all people. In 30 articles, the UDHR enumerates a set of "universal and inalienable" rights to which all people, regardless of their identity or origin, are entitled. The United Nations' Office of the High Commissioner defines these rights as indivisible and interdependent, meaning that "one set of rights cannot be enjoyed fully without the other.” For example, the deprivation of economic rights can effectively function as a deprivation of civil rights, as populations in severe poverty are largely unable to engage in the political process. These ideas resonate with the understanding of human rights in the International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESC). Together, the UDHR, the ICCPR, and the ICESC make up the International Bill of Rights.

Human rights law — and its elaboration in national policy — shapes the landscape of digital technology today. Two national policies, which emerged from the corpus of human rights law, are illustrative: the 2018 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU and the 2020 California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) in the US. "The GDPR is the toughest privacy and security law in the world. Though it was drafted and passed by the European Union (EU), it imposes obligations on organizations anywhere, so long as they target or collect data related to people in the EU.” Whereas CCPA “gives consumers more control over the personal information that businesses collect about them and the CCPA regulations provide guidance on how to implement the law.”

The UDHR is a declaration that outlines basic human rights that everyone should have. It is not an international treaty but a “soft law” that is not legally enforceable in court.

The UDHR outlines the following key rights: The right to be free and equal, the freedom from discrimination, the right to life, freedom from slavery, freedom from torture, the right to recognition before the law, the right to equality before the law, access to justice, freedom from arbitrary detention, the right to a fair trial, presumption of innocence, the right to privacy, freedom of movement, the right to asylum, the right to nationality, the right to marriage and to found a family, the right to own property, the right to a religion or belief, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, the right to partake in public affairs, the right to social security, the right to work, the right to leisure and rest, the right to adequate standard of living, the right to education, the right to cultural, artistic, and scientific life, the right to a free and fair world, and duty to your community, and the inalienability of these rights.

Human Rights Policy and Technology Platforms

While one would expect countries and companies to respect these foundational rights, perhaps unsurprisingly, many do not. Companies especially often distort or misuse these rights to proliferate harm and/or recuse themselves from responsibilities.

For example, technology companies use the right to freedom of expression as a defense when they receive backlash from allowing misinformation and hate speech on their platforms, which causes real harm to marginalized communities around the world. Beyond this example, over the last decade, technology platforms have had an increasingly negative impact on human rights. Though there are governing bodies to protect our human rights, these bodies pre-date technology which is often left unregulated and open to human rights violations.

Here are just a few examples of how technology engenders human rights violations:

- Allowing misinformation / disinformation to spread

- Lack of privacy protections / surveillance

- Censors journalists and activists

- Creates toxic environments where data can be misused against communities

- Allows gender-based violence / race-based violence

- Creates facial recognition software that is biased towards white males and harmful to BIPOC communities

- Artificial intelligence like DeepFakes can manipulate media to distort the truth

- Affords predictive policing

- Contributes to digital redlining

- And so much more!

Putting Harm Into Context

The UDHR called for freedom of religion at a time when religious creeds were routinely used to limit access to information or control the population. Ironically, continuing to uphold these principles can result in harm for some communities. For example, regardless of your perspective on abortion, religious beliefs can influence politics and laws to limit access to abortion or birth control, thus depriving women of their right to ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’ For many women, having an unplanned child would rob them of those inalienable rights, especially if they were unprepared, raped, or the pregnancy could put their lives at risk.

Another example is the right to privacy. A lot of technology companies are guilty of violating the UDHR principles with the amount of data leaks and misuse at their companies. However, sometimes, companies deliberately create technologies that infringe on privacy rights for profit. For example, Clearview AI created a non-consensual database of people and their information using facial recognition technology that is used covertly by corporations and police forces. Whereas, other times it can be an existing product or technology that is manipulated to infringe on privacy and human rights. Such as the use of Facebook to spread misinformation, disinformation, and violent extremism that escalated the genocide of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.

Privacy (as defined by Privacy International) is a fundamental right, essential to autonomy and the protection of human dignity, serving as the foundation upon which many other human rights are built.

Privacy enables us to create barriers and manage boundaries to protect ourselves from unwarranted interference in our lives, which allows us to negotiate who we are and how we want to interact with the world around us. Privacy helps us establish boundaries to limit who has access to our bodies, places and things, as well as our communications and our information.

The rules that protect privacy give us the ability to assert our rights in the face of significant power imbalances.

As a result, privacy is an essential way we seek to protect ourselves and society against arbitrary and unjustified use of power, by reducing what can be known about us and done to us, while protecting us from others who may wish to exert control.

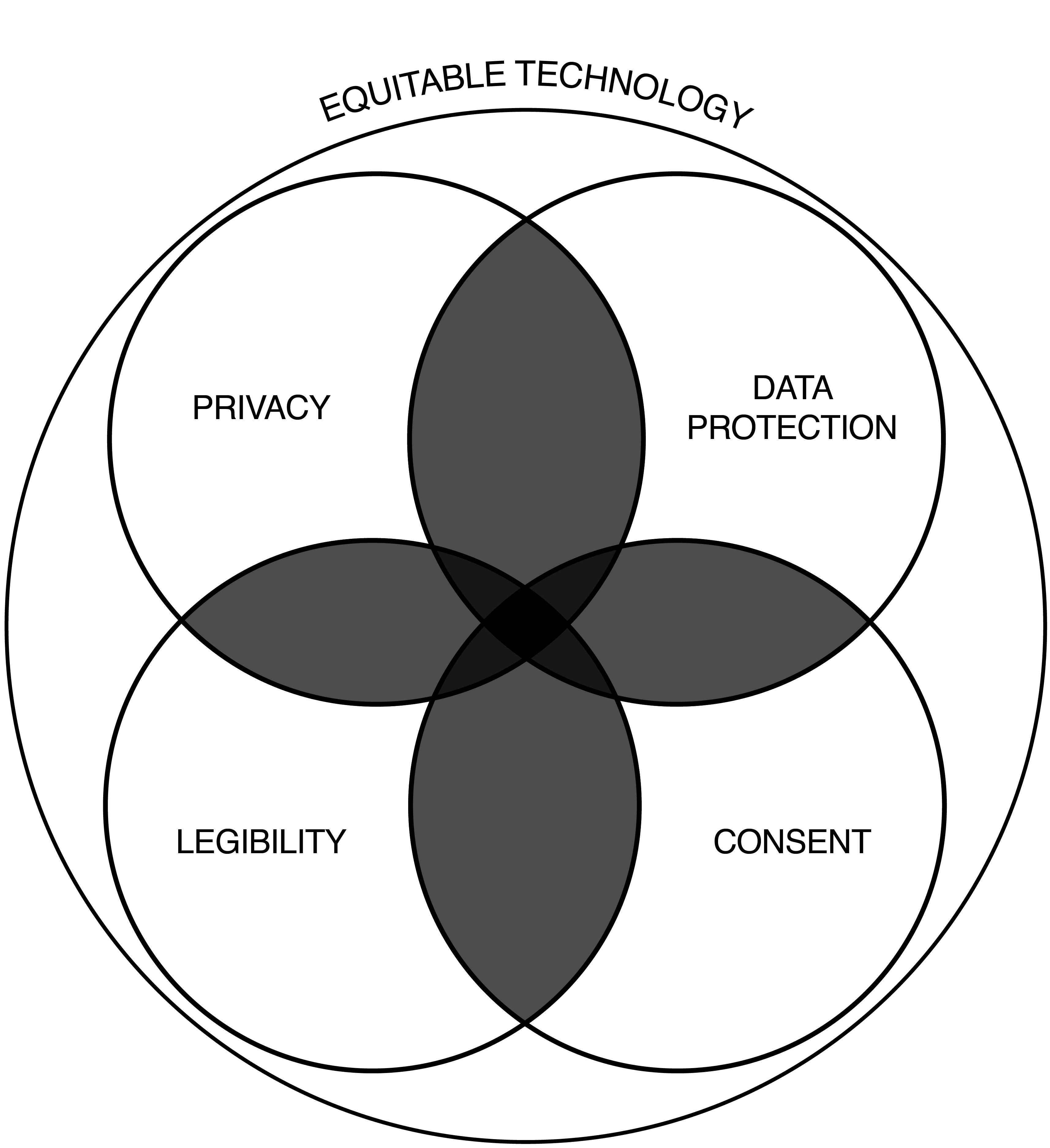

Privacy, Data Protection, Legibility and Consent, HRCD’s Guiding Design Standards

HRCD prioritizes privacy, data protection, consent, and legibility for the user and their data through the entire research → development process.

To implement these into their tools and technology, builders and designers must prioritize:

Privacy: Become familiar with digital rights in different global contexts in order to consider and respect the privacy needs of the diverse populations they serve.

Data Protection: Commit to following strict data protection standards in order to prevent hacks, data loss, and misuse. The GDPR is a great place to learn more about the world’s strongest data protection laws. To help mitigate downstream harm during the design process, designers need to step back and question whether they even need all the data they are collecting.

Consent: Get consent from users. This work cannot be done without the consent of its users and implementers must ask themselves: Is the user aware of what information they are sharing, and have they given permission to those who are further sharing it? Do they have an option to say no or revoke consent?

Legibility: Use easy-to-understand language, so a user is aware of what is happening in the product and why.

Privacy, data protection, legibility, and consent all go hand in hand to create equitable technology.

The center of this ecosystem diagram shows where privacy, data protection, legibility, and consent must converge to create ethical technologies.

One caveat: usable privacy tools are nascent. Given the increased attention to privacy, tools that promote personal security have expanded rapidly in the past few years to meet the market demand. However, many of the new products in the market are either hard to use or provide free-to-low-cost options that are easy to use but monetize the user’s data. For example, highly-secure tools for email transfer, like PGP (Pretty Good Privacy), or other similar email encryption software like GPG or Open PGP are examples of privacy-focused tools that are inaccessible to the average person. To implement, they require a certain level of technical understanding that the average person has neither the expertise nor patience to learn. Alternatively, email tools like Gmail are easy for individuals to implement but are not nearly as secure for your data and personal information. There are constant trade-offs between privacy and usability and it’s important to consider which trade-offs are acceptable and which are not.

Human Rights Policy and Design

Ethical technologies are intentionally designed to integrate concepts from human rights policy. Design travels well beyond layouts, UX/UI work, or graphic design. Design is a broader process that involves research, ideation, prototyping, and building a product or service. For example, it’s a designer’s choice whether or not to consider and respond to a community’s needs when working through these stages to build them a product or service. The choices designers make can determine whether or not their work will affect their users, for good or ill.

These principles are adapted from the article Caroline wrote for Adobe in the context of artificial intelligence (AI), but it is applicable to all kinds of software and technology.

- Human Rights Centered Design puts privacy and data protection first, recognizing that data is inherently human, always.

- It prioritizes the user’s agency by always focusing on consent and offering a way for a user to say yes or no, without being tricked or nudged.

- It doesn’t design with only opt-out in mind; it prioritizes privacy at every stage, asking users to opt-in when it comes to sharing sensitive personal data, making opting in to less private spaces the rule, not the exception.

- The design centers a diversity of experiences and puts the Global South first.

- It actively asks, “What could go wrong in this product?”—from the benign to the extreme—and then mitigates harm for those use cases.

- It views cases of misuse as serious problems and not as edge cases, because a bug is a feature until it’s fixed.

Putting HRCD into Practice

HRCD is a preventative process, committed to harm reduction. It acknowledges that something could go wrong across many stages of the design process and requires designers to map out these issues and create harm mitigation plans before the problems arise. Throughout the design process, HRCD asks “What’s the worst that could happen?”

For example, if we said, let’s build a tool that allows us to show users content from across different communities that maps to their previous clicks, HRCD would ask, what happens if that content is propaganda or misinformation? What happens if it hurts someone? If the company is not committed to filtering misinformation, hate speech, and other damaging communications on their platform, it can be dangerous so designers need to consider this while they’re building, not after it has done harm.

It challenges HRCD designers to think about how one tool or feature can be used to harass someone. For example, there is no block button on Slack, so if you are being harassed by a user, there is little you can do to protect yourself. Tools in the wrong hands can lead bad actors to use them for harm. Designers must understand how smaller, obtrusive harms can eventually have large-scale impacts. Popular apps like Grindr, OkCupid, or Clubhouse have faced scrutiny over their lack of moderation and exposure of personal details. For the all-male dating app Grindr, letting people mark their exact location makes it easier for users to find people nearby, however that same data in the wrong hands can put a particularly vulnerable group at risk.

A Tip: Leave Your Bias at the Door

No one is exempt from bias. When embarking on an HRCD process, we must reflect on our own biases. By centering the community you are working with, you can prioritize their needs over your assumptions. Don’t overcomplicate things. Sometimes the shiniest solution isn't necessarily the right one. ‘Remember the power of the PDF’, meaning oftentimes the most necessary ‘tool’ or solution a group needs is just...a piece of paper, i.e. it may not be a complex tool, but rather a process or professional support that they need to achieve their goals.

Tech Alone Can’t Fix Human Rights

This will be a concept repeated throughout the HRCD curriculum: technology alone isn’t a solution. While technology is a tool that we can use to mitigate harm, we must place that tool into context. How deeply we work with communities is far more important than throwing technology at the problem. If we don’t understand their needs and norms, we can’t offer effective solutions. While shiny new technologies are exciting, we encourage you to question the hype.

Let’s turn to the decentralized web for some examples. Web3 and decentralized technologies are all the rage right now. They have lofty goals as they are trying to mitigate harms created by Web 2.0 and harken back to and build on the utopian intentions of Web 1.0.

One example of this is Mastodon, the open-source, decentralized response to Twitter that gives communities much more agency over their experience, in part because it is decentralized. Unlike Twitter, one can host Mastodon on their own server, thus having full control over who joins their community, what content is moderated, etc. Despite usability trade-offs, the tool is intentional and responsive. It is a good example of how HRCD can be put into practice.

Blockchain is another popular technology that many claim can solve numerous problems. As human rights researcher and Localization Lab founder Dragana Kaurin said in an interview for The Open Mind podcast, “Promoting technologies like blockchain as a seemingly simple solution to complex humanitarian and development challenges oversimplifies these issues and celebrates tech as a "silver bullet" solution that will solve everything from poverty to the refugee crisis. This has led to many projects seeking technical solutions first without analyzing the challenges and opportunities, understanding the limits, potential, and threats that come with the technology in question, or including beneficiaries in decision-making. When we make decisions in humanitarian and development projects based on solutions we want to use, instead of user needs, we could be exposing beneficiaries to bigger risks, by leaving them out of the decision-making process.”

Our approach to design can and should be adjusted to fit specific contexts, audiences, and objectives. The case studies presented in this guide illustrate how those adjustments have been made across different circumstances, and they are intended to serve as lessons for readers confronting design questions in their own problem areas.

Although we cannot speak to the particular needs of every community, we can offer insights and lessons grounded in our experience and expertise. These can be adapted and reworked to serve an array of local imperatives; they are the foundations of the curriculum outlined in this guide.

In the following chapters, we progress through each stage of the research, design, and development processes.

In Phase 1, Centering Human Rights, chapters 1, 2, and 3 lay the foundations for understanding core design problems, conducting research, developing personas, and orienting your work toward inclusivity.

In Phase 2, Conducting Research, chapters 4, 5, 6, and 7 detail how to work with community partners and activists, conduct and evaluate your co-research, ideate, and develop feedback systems.

In Phase 3, Prototyping, chapters 8 and 9 walk through the prototyping and design processes of building and receiving feedback.

In Phase 4, Launching, chapters 10 and 11 focus on launching your product or service.

In Phase 5, Looking to the Future, chapter 12 focuses on launching and sustainability as a practice in technology design and shares strategies to ensure the longevity and sustainability of your project and chapter 13 recaps how and where this work is most useful.