READING TIME 30-60 minutes

- Intermediate Level

- Security Assessment Exercise

- Pen/Paper, Post-its, Computer Text File

How you conduct research, design, and build with and for communities are foundational parts of human rights centered design. In this chapter, we build on the environmental scan covered in the previous chapter that helped determine the communities’ needs and your capacity to address them.

In order to effectively help solve your partner community’s problems, you will need to begin by implementing three interrelated HRCD principles: centering and building trust with the community, implementing security protocols, and ensuring that your work and process are accessible to them. While this chapter breaks these principles out into separate sections, you can’t do one without the other. You may need to prioritize one over the other to best meet the community’s needs on a project-by-project basis.

It is essential that you have the full support of the community you are working with to understand their needs and capacity constraints, as well as get a well-rounded perspective of the problems you are trying to solve. Identifying the problems with the community is key. Common mistakes arise when you try to offer solutions without thoroughly understanding the community’s problems, for example you have not yet identified pain points, e.g. where they need the most help. Too often, well-intentioned technical experts have failed to effectively address a community’s problem because they start with their solution and not the problem they are trying to solve. By doing this, at best, those technical solutions aren’t needed, at worst, they can put the community at further risk.

- Trusted relationships: Are you responsibly building trusted relationships? For example, meeting people through trusted circles, working with them towards a common cause or goal, or having mutual interests that require an urgent call to action.

- Reputation: Do you and your organization have a trustworthy reputation with a track record of integrity?

- Feedback Channels: Have you set up secure, anonymous feedback loops to understand what your communities need and who they may want to work with?

- Equity Audit: Have you consulted with external organizations who specialize in equity to audit your work?

Working with a community partner involves trust, nuance, and respect to create a safe, non-extractive relationship. It is important that both the creator and community partners have aligned, if not the same, goals in the process.

Defining a ‘Community Partner to Build Trust’

A community partner is a group that works to advise and support your work by sharing their lived experiences and the challenges they face. Almost any group of people can be considered a ‘community’; a handful of friends, a mutual aid group with 1,000 members, a Discord server, a Facebook group, a neighborhood in a city, or a coalition of different activists could all be defined as different kinds of ‘communities.’

- Identify what type of community you are working with, e.g. online (Facebook, Discord), offline (mutual aid actions), formal (has established set of community guidelines/CoC) vs. informal (is it a loose or newly-formed group).

What to Consider When Working Together

When working with a community partner, it is imperative to understand their unique needs, threats, hopes, desires, identities, and concerns.

These are your guideposts when creating a product or service with them in order to prevent harms they may face. This process is included in Chapter 1, in the ecosystem mapping section.

- To ensure safety and build trust, you can determine the community’s needs. These needs may differ based on what type of community they are, e.g. if they are online, you may want to harden the security of your communications vs. in person, you may want to ask people to turn their phones off during your needs-finding workshop.

Public Accountability is Key

Many often believe that when a product or group is considered to be “open source”, it must be human rights-focused. However, using open source methodologies does not always lead to ethical projects.

In some cases, inherent bias within open source communities is due more to the policies governing the communities than the nature of open source itself, e.g. how much power certain members vs. others have over the platform. For example: The Wikimedia Foundation implements a series of open source projects, including Wikipedia, which are powered by volunteers. For Wikipedia, longstanding editors have more control and influence over the community than newcomers. Seasoned editors can remove or alter new contributors’ content. This can stifle the diversity of voices and frustrate newcomers when their content isn’t accepted, thus discouraging the growth of a healthy open source community.

While issues exist, they can also be mitigated by the contributor community, specifically because it is open source. This is because open source projects are transparent: their processes for how their technology is built are accessible to anyone who is interested, allowing for community input, and creating a kind of public audit which helps build trust.

From an HRCD perspective, the encrypted messaging app 'Signal' is a great example of how public accountability and transparency are infused in the processes of developing the app. Signal shares their protocols and enables others to test, contribute to, and audit the code. By choosing to make the code open source, they’re creating an accessible environment for contributors and auditors. Unlike the Wikimedia example, they create a more productive, safe, and responsive environment by having a smaller, less entrenched contributor community. Newcomers can suggest code edits on github and communicate directly with staff members about bugs, usability challenges, and ideas for new features. This increases trust and enables community-lead auditing.

Unlike open source projects, closed source projects don’t afford contributor communities any transparency or engagement. For example, Telegram’s messaging app, whose encryption code is closed source, cannot be verified, improved, or audited by the community and, therefore, is not trusted by the human rights community.

Translating Accountability from Open Source Practices to Community Practices

We can take inspiration from open source practices like public audits and participatory design to replicate this accountability process with a community. By involving the community at every step of your process and encouraging feedback, you enable the community to audit, review, reflect and connect with the product in deeper ways. This can help them feel more connected to the process and safer when using the product.

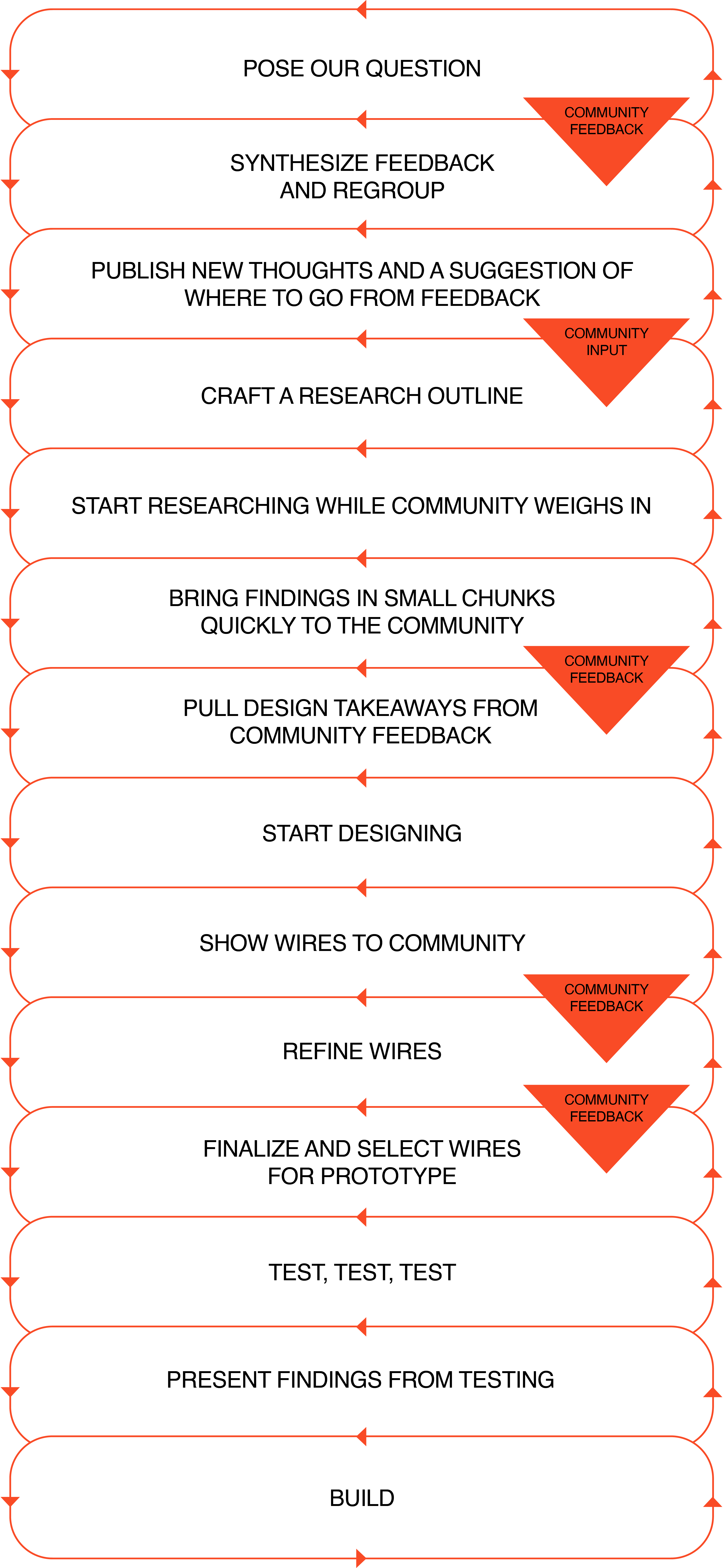

Engaging community partners in this way can translate to the following workflow:

Why do this kind of process?

The process involves a lot of community reviews! Working with a community is the best way to ensure you’re building something they’ll actually use.

Going back to our Wikipedia example, many in the design world comment on the ‘outdated’ look of its interface that lacks white space and more nuanced design elements. However, that design is intentional; through on-going user research, we found that Wikipedia prioritizes design choices to suit the contributors rather than the viewers.

Contributors are the heart and soul of the project. By tailoring the process to their needs, the site attracts more contributors, thus increasing its content and diversifying its contributor base leading to a more credible source of information across a wider range of topics despite not having a sophisticated design layout.

One Caveat: Open Source and Good Intentions Don’t Inherently Protect Human Rights

Respect, and equitable relationships are key to centering human rights with your community partner. Not all nonprofits or volunteer-run projects are doing ‘human rights’ or equity based work, and not all for-profits are bad. The context of how a project engages with community members and users is important. Some open source projects can have toxic communities or refuse to center practices to protect marginalized groups. For example, the founder of Linux would often “berate other Linux contributors, calling them names or hurling profanities [and] has also drawn criticism for creating a toxic environment and making the project unwelcoming to women, minorities, or other underrepresented groups."

Understanding Security and Privacy When Working With a Community

Now that you’ve gotten community buy-in, assessed the technical capacities of that community, set up a workflow that centers them, it is time to ensure that you are protecting the community’s rights when working with them. This means that you don’t want to inadvertently put them at risk of surveillance, doxxing, and other forms of harm online that can happen if communications are intercepted, insecure, or compromised in some other way.

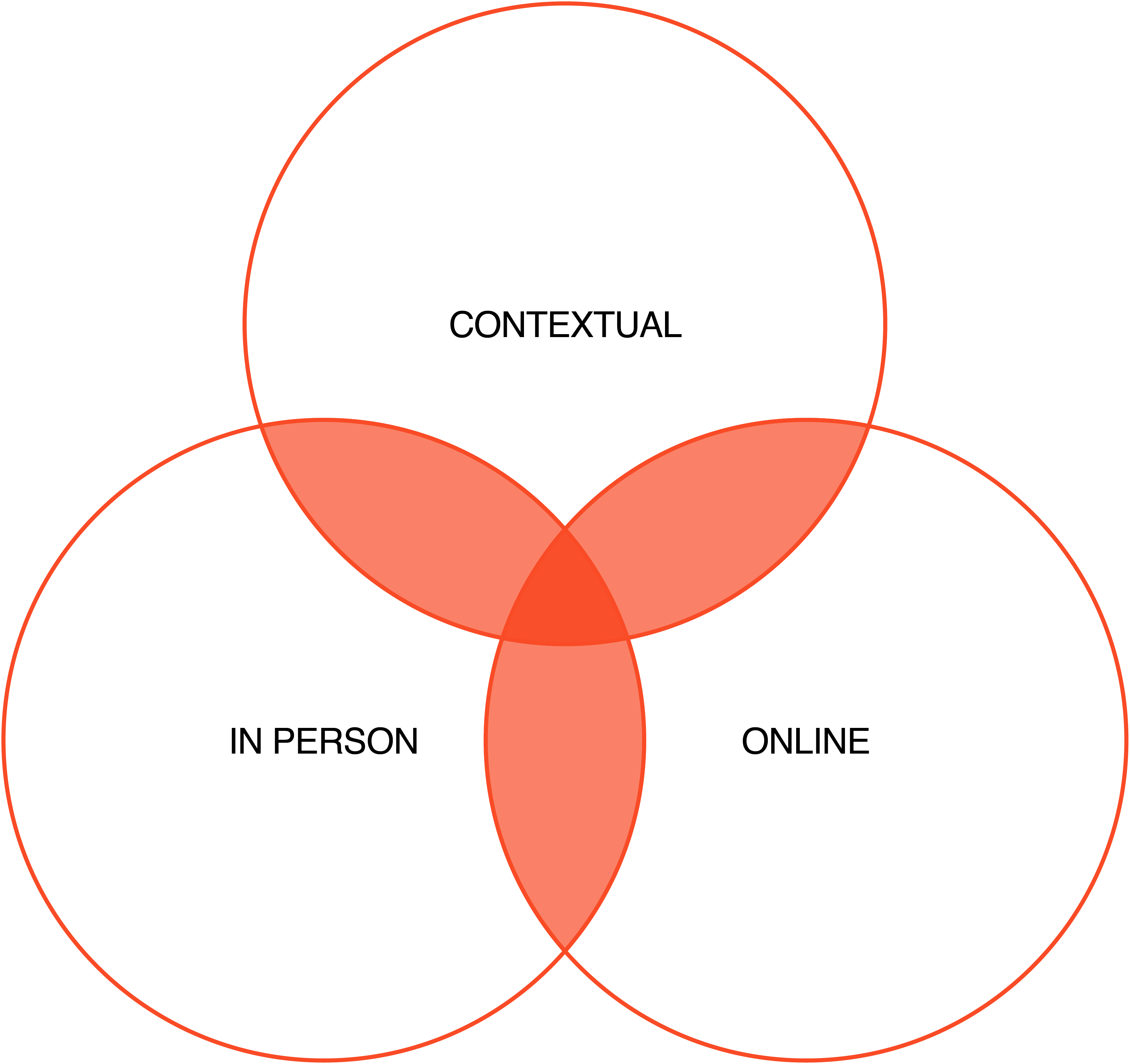

When thinking about various ways security can be compromised, you must consider security in three key contexts:

-

Contextual Security: Consider your users’ identities within their cultural and political contexts.

-

Online Security: Review how your users communicate (e.g. what tools / platforms / norms they use) and the security failures of those spaces.

-

In-Person Security: Assess their physical safety needs. Are they being surveilled at home or work? Are their phones hacked and can they record what’s being said nearby? Are they in danger of immediate personal attacks?

After you’ve taken your community’s contextual, digital, and physical considerations into account, you can now begin to implement security within those situations. For example, if you are working with journalists or activists, you would likely be working with people who are familiar with best online and offline practices that keep them safe. This is a situational consideration specific to groups who are more visible and at higher-risk of being marked. Given that they are often targeted by bad actors, many are already using end-to-end encrypted tools online to communicate or are taking measures to ensure their physical security.

If you are working with those who are likely to be targeted, but have not yet been, you may have to host digital and physical security trainings before doing deeper design and development work for them. Either way, using and setting up secure communications fosters support and acceptance with the community you serve.

Meeting Your Community Where They Are

It’s crucial to use tools that are familiar to the community you are working with. One great example of how this works in the field is unpacked by Neema Iyer, design and research expert, and founder of the NGO, Pollicy. Neema explained to us that when she was trying to do focus groups with refugees in Kenya, Zoom was not an option because it was too data heavy for their limited data plans and they were not familiar with how to use the technology. However, these refugees regularly used WhatsApp, so she was able to run the focus groups there instead.

“[Meet] people where they are on the platforms that they're [on] and then having these conversations with people from the community, or people who work with them in the community, to get to serve as their spokespeople and to give you feedback on whatever you're building.” - Neema Iyer, Pollicy

What to Consider when Co-researching and Localizing with the Community You Serve

The following outlines what you need to consider before you begin working on a project with your community to make it as accessible as possible. Localizing your work within the community’s context is a foundational first step. What this means is that you are taking language, cultural norms, and regional laws into consideration when working closely with these communities. Ideally, you will be working directly with those who are within the community.

If you are not from the community you are working with, it’s important to work closely with community leaders who can translate their needs and work in tandem with you throughout the entire research, design, development, and implementation processes. It is important that there is no room for misunderstandings or information loss between cultures and languages when you are designing products and services for these groups. Ensure that any surveys or other communications you are creating for them are vetted, localized, translated, adapted, and disseminated by a trusted community member.

Before you start building the tool, platform, or technology, you want to get to know the people who will be using them. Consider collecting and analyzing information from your stakeholders and research participants.

User research involves many methods — interviews, ethnographic field research, focus groups, surveys, etc. — that means you would retain information from others. It will be your job to protect them and their information.

Answer the following to gauge how you are doing:

Communications and Information Gathering

- I have assessed the risks of how I am storing information from my research subjects in digital mediums (e.g., storing notes in cloud-based software, or on a hard drive). I store these notes in the following spaces ****_**** because ****_****

- The medium where I store my notes is relatively secure — it is end-to-end encrypted, and difficult for third parties to access (such as law enforcement requests).

- My research does not create a digital paper trail. (For instance, I consider how metadata, like the times we have contacted each other, can expose at-risk users.)

- If I have identifiable information about my participants, I have thought about where I will store this information. I have created a plan for keeping this information safe.

- I have a list of topics I should not ask my intended audience about.

- I know the kinds of topics I should keep off-record.

Comms and Info Gathering:

- Always use end-to-end encrypted channels when you can and train contacts on the software if they are unfamiliar.

- Secure the data you keep and pay attention to protecting the identities of people in your research.

- If metadata is a concern for your audience (e.g., having evidence of you and the contact chatting or calling), do you have an alternate method of communicating?

Due Diligence:

- Partner with human rights organizations or have them as part of your research network.

- Vet subjects, including widers networks and the group you are helping.

- Learn what their most pressing problems are that you want to help them solve.

- Gather as much feedback as possible to scope measures of successes and deal breakers.

- If you keep documentation of your research process, you have considered the risks of keeping that information. (The same concerns in Communications and Information Gathering apply.)

Diversity and Inclusion:

- You use simple and jargon-free language to describe my project.

- You work closely with someone — within the group that you are researching — to be mindful about their culture.

- Always respect and consider diversity and inclusion in your process — tone, words, contact methods, etc.

- Always be empathetic and considerate.

- Keep a friendly, tolerant, and constructive space for feedback and opinions.

- Always ask for consent. Remind people of safety and security concerns.

Conducting Community-Based Co-Research to Create Responsive Technology that Mitigates Harm, From co-author, Natalie C.

“I am usually introduced to new communities who need support from trusted colleagues; primarily through the library and archival science world that intersects with activism (which is not uncommon!). Since these individuals connect with me through a trusted network, I am able to work very closely with them throughout the process, including observing them in their environment in regular day-to-day settings.

For example, in 2011, three years before founding OpenArchive, I was working very closely with an Iranian refugee archivist to understand the challenges he faced when trying to preserve footage of the Green Movement. Due to repressive laws, he had to permanently leave his home and smuggle 30,000 hours of Green Movement footage out of Iran in order to preserve and disseminate it. Working with him solidified my hunch that, in order to be useful for him and countless others in similar situations, it was necessary for me to incorporate deeper ethnographic research methods before even conceptualizing which tools needed to be built.

From an archival perspective, preserving this media is crucial and, through my work with global archivists and activists, I learned a lot more about the challenges in doing so when you're in a repressive region. This led me to become more familiar with privacy technologies that, at that time, were still nascent and difficult to use.

After witnessing the ordeal he went through to preserve and amplify his local history, we discussed various ideas about how secure archival tools could potentially help other archivists mitigate surveillance and targeting in Iran so they would not have to leave permanently when trying to get the word out.

Through his commitment to the project and our on-going discussions over the years, I was encouraged to do more ethnographic research with those who were having similar difficulties sharing, preserving, and amplifying their evidentiary mobile phone documentation. I found that engaging him at every step of the research, ideation, and development processes was incredibly helpful for us to figure out which privacy and archiving technologies to prioritize when building our secure mobile archiving app that would become “Save” years later.

Before embarking on providing solutions, it is essential to first learn as much as you can about the group you're serving, including: what their needs are, where their problems stem from, and their current capabilities, technical knowledge, and access to resources. Only by doing this, was I able to position myself to conceive of solutions that would fit well into their day-to-day processes.

Through this process, I learned how they think, what works, what doesn’t, and where my and their blind spots may be (e.g. checking my assumptions that Tor would work in Iran when it is, in fact blocked, or they may think they know how to do X, but what are they actually doing in practice and is it causing an undesirable outcome?). I learned about the whole space from multiple perspectives through observation, interviews, qualitative and minimal quantitative research which helped me to better understand what their challenges were and how I may be able to help.”