READING TIME 30-60 minutes

- Intermediate Level

- Individual quiz activity and group discussion

- Pen/paper, text pad for 5 exercises

To implement HRCD you must center the safety of the communities you work with. For this to be successful, before you begin the research phase, you must understand the physical and digital threats and risks communities face in order to ensure decisions made from design → development do not have harmful effects. Threat modeling is an assessment which allows you to map any potential harm or vulnerabilities communities might face, while challenging you to think about:

- ripple effects and potential harms that may arise downstream from the tools or services you’ve created

- harm mitigation and prevention

Threat modeling is important because every person, no matter their background, can face some kind of harm or threat. Therefore, an essential part of threat modeling is to determine the likelihood of threats or harms someone could face, and then map out a series of actions to prevent that threat (ideally) before or when it happens.

Every time you start a new project you will need to create a new threat model, even if you’re working with a community or problem you’ve engaged with before. This is because new threats arise as technology evolves.

This chapter covers how to create threat models to discover the harms your community will, or might, face. Tactical Tech’s Holistic Security Guide: A Strategy Manual for Human Rights Defenders is a fantastic threat modeling resource and starting point for you to review. We will also expand upon our discussion to include how to secure communications with your community from Chapter 2, and create a communications response to the threat model you’ve made for them.

To exemplify threat modeling best practices, we will share real-world use cases and include guest experts’ on-the-ground experiences. In these, we will review the processes that ensure the efficacy and safety of our communities, their data, and those they work with during our research processes.

If you’re new to threat modeling, don’t worry: throughout the curriculum, you will be reengaging in varying forms of threat modeling throughout the process. Once you’ve finished the curriculum, we hope it will become second nature for you to think about harm in this way and create a preventive process to respond to that harm.

Threat modeling is a structured process that seeks to: identify security requirements, pinpoint security threats and potential vulnerabilities, quantify threat and vulnerability criticality, and prioritize remediation methods.

According to the EFF, it is“a way of narrowly thinking about the sorts of protection you want for your data. It's impossible to protect against every kind of trick or attacker, so you should concentrate on which people might want your data, what they might want from it, and how they might get it. Coming up with a set of possible attacks you plan to protect against is called threat modeling.”

Once you have created a threat model, you can conduct a risk analysis. The more at-risk the community is, the more preparation you will likely need to do. We will highlight different scenarios to help guide you through real-world threat modeling and research practices that security experts and human rights defenders use. Our goal is to increase awareness about the most ethical, cooperative, and safe ways to do this work, so it sets you up for the best outcomes: ensuring the safety of those you are building with and for, and producing a product or service that truly meets the needs of your community.

There are three sub-phases within the research process that we will cover:

- threat modeling;

- setting up secure communication channels and practices to protect the community during your research; and

- re-checking your process to ensure these practices are ethical and do not inadvertently put the community at risk.

When incorporating threat modeling into your preparation for working with a community, you may quickly realize that it is safer not to move forward on the project. This would happen if you realized your work puts individuals at higher risk during the research, iteration, or implementation phases than it will help mitigate. This is valuable information that can help you assess whether you will be able to ethically work with communities or, if not, what kind of communities you are better prepared to work with.

Here we will focus specifically on what human rights practitioners need to consider during the research and ideation stages to ensure the safety, efficacy, usability, and sustainability of their products and services. Before beginning your research, it is useful to incorporate these three practices into your preparation:

- Learning the unique threats your communities face;

- Adapting your practices to mitigate these threats through behavioral and technical approaches (ex: setting up secure communication channels or choosing to meet in person without internet-connected devices); and

- Ensuring the transparency for and inclusion with the communities you serve.

There are countless examples of how technologies can, knowingly or unknowingly, harm vulnerable communities and marginalized groups when they are not at the center of the process. One particular example of this is the ‘real names’ policy.

Researcher and policy expert Jillian C. York has acutely pointed out that every few years a white man on the internet thinks he has come up with a way to ‘solve online harassment’, which usually results in him recommending that platforms force users to use their real names.

But, as many BIPOC and queer researchers, journalists, and activists have pointed out, a ‘real names’ policy further harms marginalized groups and definitely does not protect them. Early in 2014, Facebook tried to implement a real names policy. As a result, Facebook's algorithm blocked members of the LGBTQIA+ community and drag performers, and others such as Indigenous Americans from using protective pseudonyms or their actual non-western names.

“EFF has long advocated against ‘real names’ policies, arguing in particular that the way these policies are enforced subjects the most vulnerable populations (that is, people with enemies or unpopular opinions) to the most risk because of the ease with which another user can report them and thus have their account suspended…

…More disturbingly, drag performers and others in the LGBTQ community—especially transgender people—often face violent harassment, online and off. Being able to connect a legal name with an online LGBTQ identity makes it much easier for not just stalkers and harassers, but dangerous abusers, to find people offline. And the loss of ability to identify using one’s chosen identity makes it more likely that an individual will simply leave social media, thereby losing an essential source of community and information.”

If the goal of these platforms is to deter harm and create accountability, the platforms failed because they harmed the very communities they sought to protect. If these platforms had done basic user research and threat modeling before implementing the ‘real names’ policy, they would have learned that it was not an adequate solution, and actually harmful to vulnerable people.

Ironically, we’ve noticed in our own ethnographic research into online harassment from far-right communities on Twitter and Facebook, that some harassers will use their real names. Despite the goals of the ‘real names’ policy to hold people to account for their online behavior, it did not prevent abusers from doing harm.

What can we learn from this? It is essential to threat model before launching a new feature or design choice in order to prevent unnecessary harm.

This section is comprised of excerpts from the chapter “Identifying and Analyzing Threats” from Tactical Tech’s “Holistic Security Guide.”

“Putting all of the previous exercises into practice should give us a good idea of what threats we face. In this section, we will name those threats explicitly, prioritise them according to their likelihood and potential impact, and analyse their potential causes and consequences in detail. All of this will help us to identify the right tactics to prevent them, or respond to them should they happen. Our security plans, therefore, are a combination of prevention and response tactics we use to reduce the likelihood of the threat becoming a reality and reduce its impact if it does.

As with all the previous steps, this is often something we carry out in daily life without necessarily making it explicit. This process is just designed to be more deliberate and detailed, in order to foster critical thinking about our practices.

Bear in mind that this can be an emotional process, but taking steps to identify and counter the threats we face can and should be an empowering step. Threats can also be a sign that our work is effective; effective enough that our adversaries want to hinder it.”

“Let’s start with what we 'know' to be existing threats and scrutinize them. Try completing the exercise linked below to create a brainstorm of existing and potential threats.

Remember - not all the threats to our well-being and security are politically motivated or related to our work. Threats also arise from petty crime, gender-based violence and environmental hazards, to name just a few. Sometimes it is these threats that can represent the greatest risk to human rights defenders.

Perceiving threats

Our perception of threats is never perfect, but we can improve it. It may be that if you carry out the brainstorming exercise in a group that some people name threats that you haven't previously thought of, or vice versa. In the next exercise we pose some questions which may help you to think critically about your perception of threats and devise tactics for making your perception more accurate.”

This exercise is taken directly from Tactical Tech’s brainstorm exercise

Purpose & Output

This exercise is a first attempt at identifying the threats to yourself, your group or organization and your work in defense of human rights. This initial list of threats can then be refined so as to focus in more depth on the threats which are most likely or potentially most harmful.

Input & Materials

This exercise will be easier if you start with:

- your analysis of the ongoing political, economic, social and technological trends in your context

- a list of the activities or types of work you carry out in order to achieve your objectives

- your actor map, particularly the opponents

- a list of security indicators you have observed in your previous work.

Suggested materials:

- If alone: a sheet of paper or some other materials for writing.

- If in a group: a large sheet or flip-chart and writing material.

Format & Steps

Consider and write down all the potential threats to yourself, your organization and your work. It may be helpful to categorize them beginning from each of your activities or areas of work. Remember: a threat is any potential event which could cause harm to ourselves or our work. Don't forget to consider potential threats to your information security and threats to your well-being, political or otherwise.

Create a list of these threats. If you find it difficult, consider your opponents and the ways in which they have acted against other human rights defenders in the past. Analyze your security indicators and consider whether they represent a concrete threat.

Observe any patterns that emerge in the threats you identified: do they relate primarily to certain activities of yours, or originate from certain opponents? This will be useful when it comes to security planning (i.e. by planning particularly for certain activities, or dedicated plans for engagement with some actors). Keep this list for analysis in the following exercises.

Remarks and tips

If the list is somewhat long, it may be overwhelming to consider these potential threats. It may also be a challenging exercise as we may not know how realistic we are being. It's important to remember that political threats always originate from a certain actor or set of actors who see their interests potentially threatened by you and your work. In a sense, threats are a sign that your work is effective and that your opponents fear your work. While it may be a moment which inspires fear, clearly recognising the threats you face should also be a moment of empowerment. Acknowledging these threats and the likelihood of their occurrence allows you to better plan for and potentially mitigate the damage caused to you or you work, should one of them occur.

Analyzing risk, prioritizing threats

"As discussed above, threats can be viewed and categorized in light of the following:

- the likelihood that the threat will take place

- the impact if and when it does.

Likelihood and impact are concepts which help us determine risk: the higher the likelihood or impact of a threat, the higher the risk. If a threat is less likely or would have a lower impact, the risk is lower.

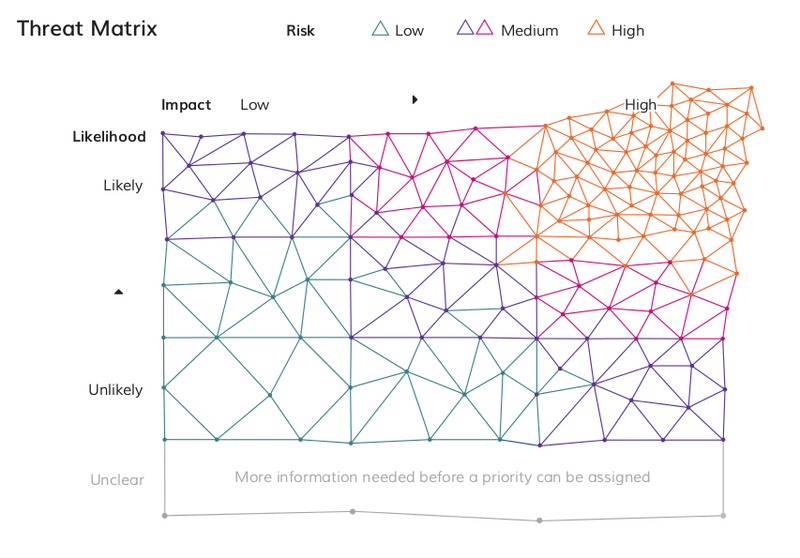

Categorizing threats in this way can help to keep us from feeling overwhelmed and keep our perception of threats realistic. Likewise, it is a good idea to share what we find with others to check our perceptions. It may help to visualize the threats you have listed on a 'threat matrix' such as the below:

By considering the threats we identified in light of their likelihood and impact, we can then move towards a deeper analysis of them, the conditions required for them to happen and their potential consequences, which will aid us in planning to react to them. Download the full length chapter to learn more on how to define likelihood and impact and apply this to the threats you have listed.

Declared threats

It is common for human rights defenders at risk to receive declared threats from their opponents, e.g. a message from an individual, group or organization that openly expresses their intent to cause us harm. The intention of these threats is to compel us to stop our work (at least temporarily), to punish or hurt us and discourage others in turn. Such messages constitute a special kind of security indicator because they already have a psychological impact on us and might well correspond to an actual threat.

Generally, 'declared threats' are intentional (they are made with a clear intent), strategic (they are part of a plan to hinder our work), personal (they are specific to us and our work), and fear-based (they are meant to scare us into stopping our work). Declared threats may also be made or implied in our opponents' public statements or through judicial harassment or proposed legislation. They are very effective as well as “economical” because they may achieve their goal without having to carry out the actual threat made.

It is important to keep in mind that while some declared threats may have concrete implications, others are intended to create new unfounded fears while no actual action to harm is planned. When analyzing declared threats, it is helpful to go back to your actor map and consider the resources and interests of the adversary in question to know whether a genuine threat is posed. You can find concrete steps for analyzing declared threats from the Front Line Defenders Handbook on Security in Annex B.

Having examined what threats we face, and considered the risk they pose (based on likelihood and impact), the next step is to create an inventory of the most high-priority threats, and analyze in detail the nature of each threat: their causes, ramifications and sources, as well as the required resources, existing actions and possible next steps you can take. This activity will lay the groundwork upon which you can build your strategy to reduce the likelihood of the threat occurring, and its impact if it does.

Remember that all of this will change over time, and therefore revisiting the process is very important. Determine how often you should revisit these lists and set aside time aside for it.”

This exercise is taken directly from Tactical Tech’s brainstorm exercise

Purpose & Output

This exercise will help you improve your recognition and analysis of threats in order to respond adequately. You will learn to recognise your own blind spots and missing processes for identifying threats as well as creating processes to fill these gaps.

Input & Materials

Use the list of threats from the Threat Brainstorm exercise above for this exercise.

Format & Steps

Individual reflection or group discussion

Ask yourself or the group the following questions:

- Were there any threats which you discovered or which were mentioned by others, which you wouldn't have been aware of previously?

- If you did the exercise in a group, was anyone else surprised by the threats you mentioned? Why?

- How long do you think the threats you identified existed before you became aware of them?

- How might you have become aware of them sooner?

- How do you communicate in your group, with your colleagues about them?

- What makes them feel more or less serious?

- Can you identify any threats that feel more serious than they might actually be?

- If you are working with a group: what are the differences in your answers to the above? What makes you think of the same threat in different ways?

Remarks & Tips

It can be overwhelming listing all the threats you face. Be sure not to rush this exercise and to allow space for people to express their feelings as they go. If you find this exercise useful, consider making it a regular (weekly or monthly) exercise.

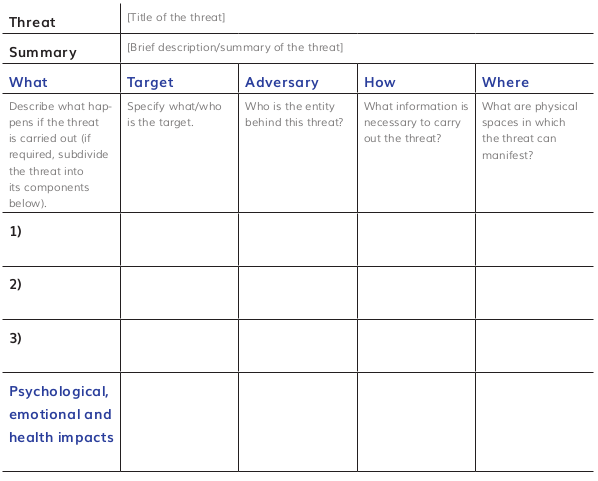

“If you wish to record the results of the exercise in writing, you could use a format like the one below:

Once we have carried out this analysis, the next step is to look at ourselves and consider how our existing practices, resources and other capacities may protect us from them, and how the gaps in our practices and resources, along with other vulnerabilities, may make us susceptible to them.”

This exercise is taken directly from Tactical Tech’s brainstorm exercise

This exercise will help you prioritise threats and divine the causes, ramifications, sources as well as the required resources, existing actions and possible next steps. The output of this exercise is an inventory of your prioritised threats in some detail, which will be used in Chapter 3.1 Responding to Threats to help you create plans of action.

Input & Materials

- Actor and relational maps

- Information ecosystem

- Security indicators

- Impact/Likelihood matrix

- Pen and paper

- Flip-chart

- Markers

Format & Steps First, beginning with the threat brainstorm from the previous exercise, consider the threats listed in terms of their likelihood and impact. Make a selection of those you consider to be most likely and as having the strongest impact to use for the next exercise.

It may be useful to separate and organize threats according to particular activities (e.g. separating those which specifically arise in the context of protests from those which relate to the day-to-day running of your office).

Start with what you consider the highest priority threat, based on the impact/likelihood matrix, and using the example template provided, elaborate (individually or in a group).

Write down the title and summary of the threats.

For each threat, if it is a complex threat, you may decide to divide and analyze sub-threats (for instance, an office raid and arrest may be easier to analyze if separated to include the numerous consequences each would include – potentially arrests, confiscation of devices, judicial harassment, etc.). Use the rows to expand each of the below per sub-threat.

Work through the following questions for each threat. It is possible that some threats are complex, and some of the answers require their own space. Use as many rows as necessary. If, for instance, a threat constitutes an attack on a person, as well as the information they are carrying, you may want to use one row to describe the informational aspects and another for the person in question.

What: Describe what happens if the threat is carried out. Think of the impact it might have on you, your organization, your allies. Include damages to physical space, human stress and trauma, informational compromise, etc.

Who: Identify the person/organization/entity behind the threat: Referring back to the actor map, you can focus on information regarding this specific adversary:

- What are their capabilities?

- What are their limitations to carrying out these threats?

- Are there neutral parties or allies that can influence them?

- Is there a history of such action against you or an ally?

Whom/what: identify the potential target of the threat; specific information being stolen, a specific person under attack (physically, emotionally, financially), material and resource under threat (confiscation or destruction of property).

How: What information is needed? What information is necessary for the adversary to be able to carry out the threat? Where might they get this information?

Where: describe the place where the potential attack might take place. Does an attacker need access to the same location as you, as is often the case in a physical attack? What are the characteristics of the location in question? How can we help you to keep safe? What is more dangerous about it?

Elaborate on the psychological, emotional and health factors as they relate to this threat, including the effect your stress levels, tiredness, fear and other factors have on the potential occurrence of this threat. Consider:

- How might your current mindset affect any planning and contingency measures being carried out?

- Does this threat take place in the context of a particular activity? What kind of mental or physical state do you find yourself in during such activities? What are some best practices which may protect you, or what might make you more vulnerable?

- What elements of your behavior or state of mind may actually increase the probability of this happening, or its impact?

The above text is from the Tactical Technology Collective’s The Holistic Security Guide’s Chapter “Identifying and Analyzing Threats.” That chapter and related work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Now that you’ve mapped out the harms that threaten our community, you can start setting up secure communications to keep your community safe when you connect with them online, offline, or otherwise. This is an essential first step before you begin your research with them. Once you’ve done this, you then must ensure your work environment is equitable.

What to Consider When Starting Your Research

No matter who or where you are in the world, there are various threats to consider when working with others. For example, expansion of surveillance technology, the internet of things, and potentially malicious algorithms are creating new threats for anyone who uses the internet. If you are working with vulnerable or marginalized groups, it is key to mitigate harms caused by these technologies. Doxxing is just one example of how bad actors can reveal personal information online (with the intent to incite offline harm) without the target’s consent. Even if you don’t deem the groups to be at high risk, research between an organization and a community should be protected for the best interest of both parties.

Once you begin to assess your community’s threat model, you may see patterns of where they are most vulnerable. For example, while widely-used apps like WhatsApp and Telegram claim they are “secure,” both have been compromised by various bad actors. After Facebook acquired WhatsApp, on February 8th, 2021 it forced the messaging app to change its terms of service, forcing users to share their data with Facebook.

In the case of Telegram, hackers infiltrated the platform and leaked 500 million users’ data online. While Telegram employs some security measures, it is not end-to-end encrypted or open source, thus vulnerable to hacks. Check Point is a software solutions company that provides cyber security solutions to governments and corporations globally. They issued a warning against Telegram saying that it has “tracked 130 cyber attacks that used malware managed over Telegram by attackers in the last three months... Even when Telegram is not installed or being used, it allows hackers to send malicious commands and operations remotely via the instant messaging app.” It can do this because the malware is sophisticated and sent through email messages where it connects with the bots in the Telegram app. The most insidious part of this story is that Telegram purports to be a ‘secure’ messaging app when it is not, giving users a false sense of security.

Mitigate Surveillance Threats

Even if those you are working with are not being surveilled or targeted, by centering the most at-risk communities throughout your work, you will ensure anyone who uses your tool or service is protected.

Although privacy tools are increasingly easier to use, it always takes time to integrate them into your workflow and train your communities to use them. When it comes to the security of your community, the small investment of time to do this right is one of the most important steps you can take to protect them from harm.

- In-person: If you are meeting in person, ask participants to turn their phones and computers off and take notes on paper.

- Text / Group Chat / Video / Phone Calls: If you need a secure chat app that offers a way to connect with many folks in real time, the Signal app is currently the gold standard. It is not vulnerable to hacks or data breaches because: _ it is open source and auditable; _ it provides end-to-end encryption; _ it has no centralized server, and thus doesn’t store your data; _ it is only hosted locally on your phone or desktop app, so there is simply no central database to hack. If you are unable to use Signal, look for the same features in other apps.

- Email: PGP (or pretty good privacy) is very secure but equally as difficult to use, so if you are unable to set that up with your community, many easy-to-use email providers now offer secure email services. Use up-to-date recommendations from the open source community such as the Foss’ 2021 guide to stay on top of which services are effective and which are not. Look for providers who: _ use end-to-end encryption; _ employ two-factor-authentication (2FA); and * have a reputation free from security vulnerabilities or breaches.

- Collaborative Documents: Keep an eye out for tools that offer encryption and decryption in your browser. This means that there is no centralized database containing your information from shared documents, chats, and files, which are unreadable outside of the session where you are logged in. Tools such as Cryptpad currently offer these features.

To help your communities stay safe, review the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Surveillance Self Defense guide to find vetted tools for creating closed-loop, secure communications channels.

These resources age quickly, so make sure you keep an eye on updates!

While we have primarily focused on external threats, internal threats can be just as, if not more, harmful. To mitigate internal harms, often born of resentment / frustration / exclusion, ensure your work is transparent and your communities and internal stakeholders are deeply involved in your process.

- Transparency and Inclusion:

- create shared documents and communications channels that everyone can access and edit;

- ensure your decision-making process is consensus-based; and

- develop clear guidelines and safeguards to protect that process if it is violated.

- Create a Code of Conduct: Create a code of conduct for your organization that you also share with the communities you work with, so everyone knows what types of behaviors are acceptable and which are not. A great example of a CoC for open source projects is by the Contributor’s Covenant. While it is geared towards open source projects, it can be extrapolated to the ways stakeholders interact more generally.

To gain more insight about the abuse or harassment someone has faced, ask the following questions:

- What happened?

- What devices did it happen on (if any)?

- This can help you determine if other devices were affected or how to patch the vulnerability, etc.

- Does anyone else have physical or remote access to your device that this happened on?

- What time did the event occur?

- This helps you contextualize the event and possibly learn why this happened (i.e. was it after the person tweeted something publicly? Attended an event? After a mass email leak? etc.)

- How often does this happen?

- What information did you see in the attack (like a popup/screen/text/image/etc.)?

- This is useful because you can often Google the exact language to learn more about the exploit.

Once you’ve answered these questions, you can create a safety plan, a harassment response plan, and an investigation plan, in order to figure out how to get help and prevent further harm.

Threat modeling helps prevent tunnel-vision when it comes to potential harms. You are challenged to consider all possible harms to all communities when building new features, tools, and services. The following case studies show what can go wrong when organizations do not think broadly about harms their new features will cause. While they are trying to solve one problem, they inadvertently create ten new ones.

In early August 2021, Apple announced a new plan to combat child pornography by scanning images on every iPhone. However, privacy experts quickly pointed out that Apple’s decision could give law enforcement, governments, and hackers new ways to surveil people, including journalists, activists, and dissidents.

Once a backdoor is built, anyone can kick it in.

Apple promised it would not grant external access to individual’s phones or acquiesce to governmental demands. One month later in September 2021, Apple and Google caved to pressure from the Russian government. The Verge reported that both “Apple and Google have removed jailed Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s voting app from the iOS and Android stores under pressure from the government. The New York Times reports that the removal followed threats to criminally prosecute company employees within Russia.”

In another example, sometimes companies require state or country identification cards to help prove the identity of a user. These cards contain highly sensitive data and if misused, can have grave consequences to the holder.

Companies deciding to enact this requirement, need to ask themselves:

- Can they guarantee there won’t be a data leak, e.g. that they can safely store this sensitive information?

- What would happen if this database was made public?

- Do they really need to require these IDs for verification?

- Are there other kinds of verification they can require instead?

Truthfully, the company’s answer will depend on what its tool or service is. For example, it may be more justifiable to require an ID if the company is creating an app for the government to verify COVID-19 vaccination status. But what if the app is just for accessing email? Can companies add 2FA, a YubiKey, or a Google authenticator to ensure that whoever is logging into that email account is the right person, without having to submit sensitive information.

These two examples may seem disparate, but they are linked.

Both illustrate how:

- without safe and secure tools and services, we can’t ensure safety for ourselves and others;

- we cannot assume companies and governments have our best interests at heart; and

- there can be unintended negative downstream consequences of design and development choices.

When you and your community work together to create tools and services there will be varying downstream effects, depending on your context. These effects can ripple across many different communities that may use the same tools or resources to mitigate different problems. As builders, designers, and researchers, we can avoid these pitfalls by threat modeling effectively.

Threat modeling how your work can be abused in different environments is a necessary step that helps prevent you from inadvertently causing serious harm.