READING TIME 20-30min

- Intermediate Level

- Individual quiz activity and group discussion

- Text files and paper/pen, post-its

This chapter explains how to create ‘user personas’ to map their needs and behaviors in order to build more responsive work with them. Designers create these to better understand how their users will engage with their products and services. This process incorporates all the work you’ve done so far to center communities, map the ecosystem, and conduct research. It requires you to use first the insights you’ve gained from first hand experiences, community participation, and mixed methods research in order to develop these insights into user profiles (personas).

Personas, Defined

Before we learn how to create and use personas, we need to understand what they are and learn about their limitations.

"User personas are [anonymized] archetypical users whose goals and characteristics represent the needs of a larger group of users." User personas are modeled after a particular person, but also incorporate fictional aspects that you use to create ‘ideal personas’ to compare and contrast with the ‘actual personas’. You will present a persona in a one to two-page document that describes their behavior patterns, goals, skills, attitudes, and background information, as well as the environment in which they operate.

For example, say you’re building a way for journalists to send encrypted messages and videos to each other. You would first create a series of different user personas for journalists in various countries that include the unique type of harms they are facing and their messaging habits. Then you would get more granular and create user personas of journalists that include more specific characteristics such as their gender, types of devices they use, and their levels of technology background. These personas can illustrate their personal and professional experiences, issues that they face within a country or their work, and general capabilities when using digital tools. This will help you map your work to suit their unique identities, motivations, and capacities so that you can design the best product for your target audience.

Personas are a great way to ensure that you are incorporating your research insights into your work to more effectively address your community’s needs. As a bonus, personas can also help you create a threat model! By grounding your personas in your prior research and ideation, you can learn how someone might misuse or misunderstand your work and help prevent future harms downstream in this step before you actually develop the tool.

They will also help you learn how to address specific needs they have now that you know more about their daily lives. For example, a persona that uses an Android phone that is on a 3G network informs you that your work needs to be Android-compatible and low-bandwidth so that it is accessible to that particular user.

Lastly, by anonymizing your community members in your personas, you can share a lot of your users’ personal information with other collaborators while protecting their identity.

However, personas are only as useful as the research that informs them.

While personas can help you create a roadmap for your work and help you better understand your potential audience, creating them is challenging when your research isn’t sufficient and can lead to inequitable representation.

Design Justice by Sasha Costanza-Chock highlights how, more often than not, user personas are commonly created without doing the appropriate research. Without truly understanding who you are serving through deep ethnographic interviews and observations, you may unintentionally reinforce stereotypes and your own assumptions.

Constanza-Chock points out that user personas are often "created out of thin air by members of the design team" and are based on "assumptions and stereotypes."

Constanza-Chock adds that these assumptions ultimately objectify the user, resulting in "product development to fit stereotyped but unvalidated user needs."

As creators and researchers, we’ve seen bad practices modeled throughout projects. Often, designers will choose a persona from a persona library. These personas have little to no information about how they were developed or how old they are, which is critical to understanding their validity. Moreover, these types of personas focus on surface-level information such as a person's age, gender, race, and technical background, but don’t take into account key structural contexts that impact them. For example, ability, political, financial, regional, cultural, religious considerations, which greatly help inform how your work will affect them within those scenarios.

Personas based in insufficient research lack the contextual information that makes them useful for product mapping. When developing personas, it’s important to include deeper levels of information into your research such as the threats a user faces, how they use technology, what their desires are, and what frictions they encounter when using current tools/services available to them.

Mapping out a user's needs can help designers understand their experience, especially when working with multiple teams and community members.

This research allows you to discover and gain deeper insight into the structural harms the community you're working with faces. In order to use personas with at-risk groups, the HRCD process reminds us that we must expand the existing definition of a persona and be careful not to oversimplify it.

In comparison to the standard persona which is often limited or prescribed, an HRCD-focused strategy must create more robust personas through deep, in-depth qualitative and/or participatory research.

An HRCD persona also includes necessary information to help inform your work to make it as safe, secure, and intersectional as possible.

You should update your personas every few years and timestamp them so you know when they were conceived or updated. You should also note where the information was taken from or how it was used in other projects. We also encourage designers to make new personas for different projects, instead of simply reusing them.

You can use the older personas to compare or test how they fit into your threat model or test research, but older personas should not be used in lieu of creating new personas.

Remember: personas are an iterative process.

Throughout your research and design process, you should continuously go back and compare/contrast your personas with actual user flows throughout your projects and iterate on them. Personas can guide you through your process as new research, changes or events occur. Much like how real-life and research continues onward, your personas should also evolve over time.

Imagine you are building a secure and encrypted messaging tool for journalists that provides a safer alternative to WhatsApp. Given your global potential audience, it's important to ensure that the app is accessible, usable, and works on all devices.

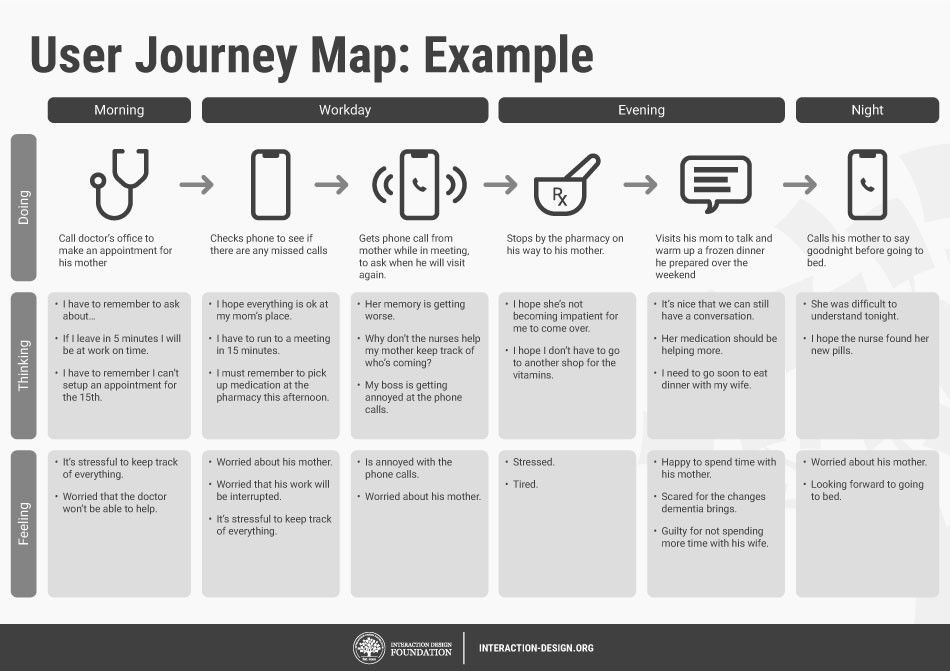

Personas can help remind you of real-world constraints, and also help you document and build up necessary internal information about why you’re building something, and the needs of who you’re building with. Once you’ve created your personas, you can now make a journey map to outline their day-to-day tasks. This is helpful to see where your work can benefit them in their specific situations.

Natalie Founder and Executive Director of an an experienced research and development organization dedicated to the ethical collection and long-term preservation of mobile media.

Natalie shares a real-world example of how she created personas while working with Human Rights Watch (HRW):

HRW receives documentation of human rights abuses from the field to help survivors achieve accountability and justice, develop advocacy and outreach campaigns, and build evidentiary archives for the communities they work with. This media includes survivor interviews, videos, images, and first-hand documentation.

To create personas for each use case, HRW identifies the people and stakeholders sending and receiving media from the field. Pulling directly from various user interviews, Natalie's team crafts four personas: the researcher, the archivist, the videographer, and the technologist. Next, to better understand the problems from these four specific perspectives, the team creates a venn diagram of overlapping needs, wants, and security threats to better understand their entire workflow.

The team is able to create harm-reductive journeys for their personas by centering security challenges that focus on real-world harms, and how we can combat them to achieve the ideal scenarios.

By comparing the real-world and ideal scenarios, the team is able to see where the products and tools fall short, and how to change or improve them to prevent harm.

Kimberly Seals Allers, Founder of Irth

The following is an excerpt of a conversation, cut and edited for clarity and brevity, between Caroline and Irth Founder, Kimberly Seals Allers. Irth is a social change tool designed to address the high mortality and the infant mortality crisis among Black mothers in the US, a symptom of systemic racism and bias in care. Irth is a Yelp-like review and rating platform for Black and Brown women and birthing people to find and leave reviews of their OB-GYNs, birthing hospitals, postpartum experiences, as well as their pediatric care, to bring accountability and transparency to the medical system.

Caroline:

I’d love for you to share tips for how you found and collaborated with these communities.

Kimberly:

You have to start with the right framework. Whatever the question, the answer is in the community. Too many times, we feel like we're trying to help save a community. I always felt like the community could save itself and I'm just trying to help them by providing a tool. You're not trying to save the community. You are actually leveraging your expertise with their needs. For me, Irth is a tool to leverage the power that's already in the community. This is critically important, whatever the question, the answer is not in the research or medical journals, it's in the community. So, ask yourself, what are you doing to be in touch with the community?

Next, you will need to stretch yourself. When people try to test an idea on the Black people that they know, the Brown people they know, the Indigenous people that they know, that is always a fail. You have to be willing to get to know the people that you claim to serve. It sounds really simple, but very few people are doing this correctly. And be respectful, don't tokenize people. I get calls from many white design teams, white tech companies, that all of a sudden are very interested in Black maternal health. They have no history of doing this work or caring about this issue, but all of a sudden, they care, and they want to bring on a Black person to help them tap into this market and provide them [access].

This takes a lot of work. It took a lot more work for me to be on the ground in New Orleans, listening to people, standing out in front of churches, putting up a tent in a Walmart parking lot, going to hair salons and nail salons and standing in strip malls. It's a hell of a lot of work. I mean, quite frankly, people don't want to put in the work, but you gotta put in the work. So be willing to put in the extra work. It is not going to be as simple as a focus group. And you have to be willing to put in the work. So that's an important part of understanding how we can build a different co-design process.

When people are saying that something needs to change, you actually have to listen. There were lots of things that I thought would be a good idea and no one else in the community thought it would be a good idea. So listening to the community is key.

Usually persona development is done with a group of people, not alone in isolation and not with just one person so that you can get a better idea of everyone who is involved. Start by bringing your community and team members together.

Together, you will develop a persona using demographic information. Remember to include all the structurally-specific information we covered above. The point is to make them real. A good way to start is by identifying people that can be grouped into a set of personas. For example, at Human Rights Watch, the research and development organization identified four main groups of people who needed a secure mobile archiving application that will help them preserve field media while also protecting all involved. Natalie chose to focus on the four groups central to the work of collecting and preserving evidentiary media: videographers in the field collecting survivor testimonies and other evidentiary documentation; the archivist(s) working to intake, keep organized, and make the media accessible to those who need it; the researchers who are area experts in the field of human rights work affecting the region and are responsible for recording testimonials from the survivors; and technologists who create tools and platforms for the organization to use.

You can use this template to map out your personas > Create a persona based on the following information:

-

A pseudonym (this will make easier to refer to the persona in conversations with your group)

-

Age

-

Location

-

Education

-

Occupation

-

Race

-

Gender

-

Sexuality

-

Religion

-

Disabilities

Then tell us more about the persona:

-

What do they like to do?

-

What is their relationship like with their family or peers?

-

What are their goals?

-

What motivates them?

To achieve a deeper level of understanding, we use the HRCD framework to ask the following questions: How does the persona relate or fit into your problem statement? For example, if you’re researching something related to technology, how do they use the technology? Why do they use technology in a particular way? This is a space for you to confront your own assumptions as well.

Answer these additional questions in the persona:

-

What are their desires and wants in relation to your problem statement?

-

What do they dislike, or what does not work well for them?

- If you’re building something, have there been previous failures and why?

-

What do they need? (Again, what do the community members say they need, not what you think they need)

-

What are the users’ real-world constraints, burdens, and frictions?

-

This is probably the hardest one to answer, because it relates so specifically to your user group. For example, when researching online harassment, a lot of potential tools or workflows place a high amount of burden on the user when that user is already in an emotionally heightened space. Facing harassment is extremely stressful. Trying to file a harassment report or find security settings that are buried deep within an app can put further stress on the user. Requiring the user to file a police report may be untenable and inappropriate for that user; after all, the police are not safe authorities for many users to engage with. But also, leaving one’s house, and filing a report takes time a user may not have. This section is asking you and your community to reflect back on the burdens and friction a user may have when trying to help them solve their problems.

-

What are their real-world technological constraints?

-

Internet connectivity issues

-

Electricity issues

-

Apps often not localized in their language

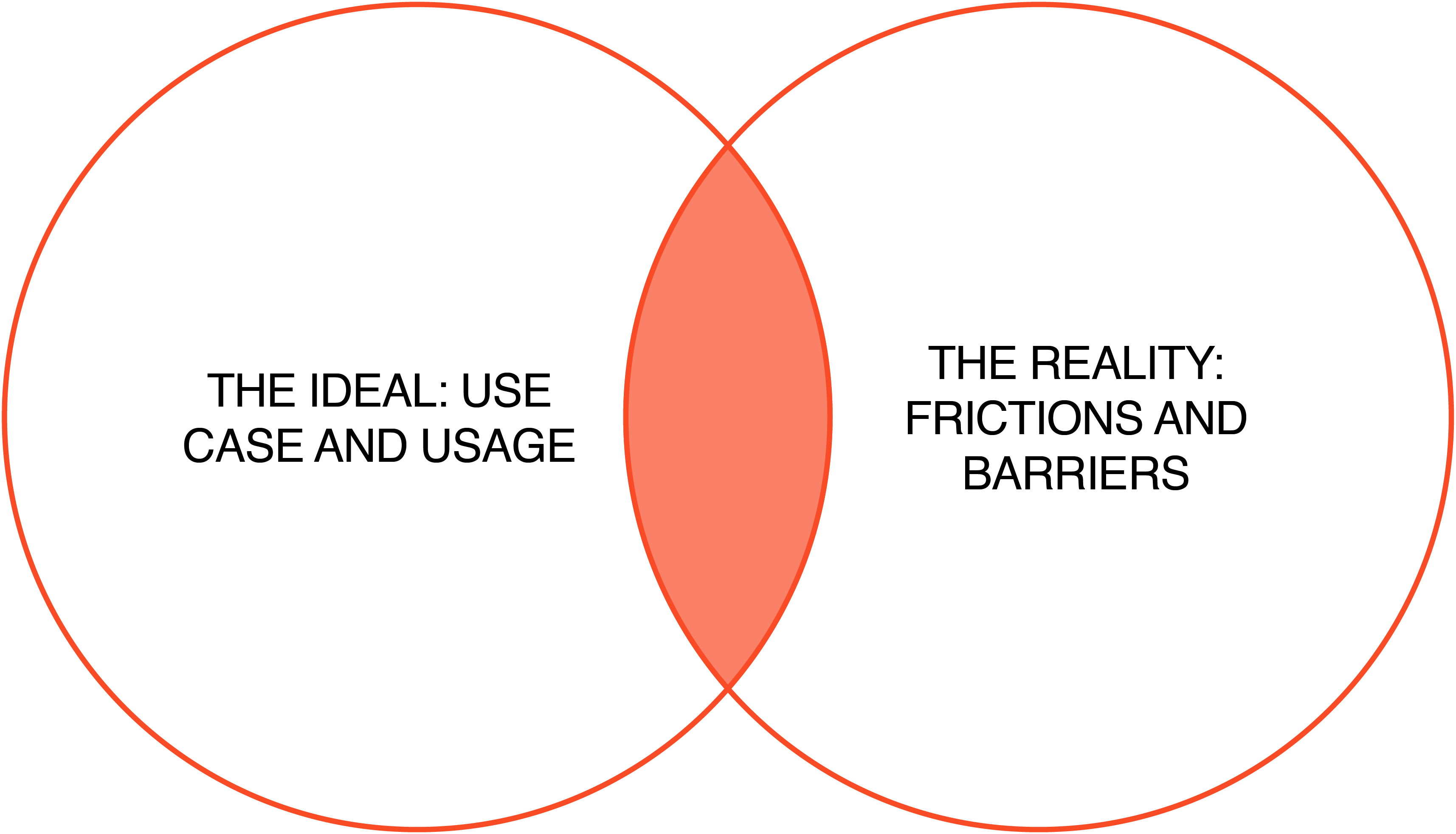

The goal of this exercise is to compare an ideal scenario in your community to the reality and frictions that you’ve found within your research. However, we need to heavily caveat this section. In a non-HRCD process, use cases are often oversimplified and reflect real-world stereotypes. To avoid creating shallow use cases, use your deep research to build out more accurate ones. Let’s use the Human Rights Watch example from the text.

For example: you may not be able to reconcile the actual personas with the ideal personas, but you can make contingency plans for what they can do if your tool/process doesn't cover their need (e.g. if they don’t have reliable WiFi access, they can send hard drives in the mail).

In Natalie’s work, she researched how people share first-hand media with HRW to create four personas that include the archivist, researcher, videographer and technologist. She found their ideal workflow of sending “large media files over WiFi'' was challenged by the fact that “WiFi is not always available to all involved”. Through this process, she was able to identify where accessibility issues may occur and why and then adapt the tool to better suit the needs of all involved.

To identify potential barriers your personas will face in your project, use this venn diagram to map out your ideal and realistic personas to understand where they converge and where they don’t.

Outline the harms and threats faced by your community by answering these questions:

- Are there key historical or cultural contexts and facts that we need to know?

- This can be highlighting regional-specific bias or histories of harms

- How do they impact the community's behavior?

- Do they face any harms specifically tied to their identity?

- Go through the basic information list above to map this out. Some users will face harm depending on where they live, their occupation, race, gender, religion, sexuality, or all of the above.

- What are the harms they face online or from specific technologies? How do these harms transfer outside of digital spaces?

- This could be similar to the above, but it gives you a chance to get more specific. For example, maybe someone is an activist who faces coordinated harassment campaigns related to their work or their gender. Maybe those harassment campaigns come from different governments or from everyday people. You will need to identify the who and what of these harms to get an idea of how to best help. Is the harassment related to their activism or race, sexuality, or gender? Is it harassment from their community, governments, etc. List out these points.

- What harms do they face offline?

- Assess how they are targeted offline. Has someone mentioned any offline or physical threats? For example, do these prevent them from traveling getting a visa, etc.

This exercise focuses on how to link different personas that face different, but related, harms. This exercise will also help you understand how a potential harm can impact personas differently. Once you create the personas, you can group them around problem areas. Problem areas are points in the workflow where the persona is either put in harm’s way, faces frictions around access to technology, is unfamiliar with the tools or processes being introduced, or finds that the work violates their cultural/religious practices.

You can start identifying the problem areas by asking yourself the questions below. This can be done by printing out the personas and using markers, post-it notes, or even string, to group them together around thematic issues or harms.These can be listed out on separate post-it notes or pieces of paper so you can better see the landscape of issues your personas face.

Ask yourself:

- How are the harms different between personas?

- What are their security threats, both online and offline?

- What are the most important needs to center? How do we know?

- Get community feedback on the list of needs you created, including a representative from each user persona group

- Which problems can you help them mitigate (improving security)? Which problems can you not (laws, policy, bias, etc.)? Understanding what you can and cannot help with enables you to scope appropriately.

- What are opportunities?

- This can be an area to ideate and work with your community. You can start listing out ideas to present back to the community and use this as a jumping off point for ideating.